Yes, there’s a 67 in here. No, it’s not the 67 that most people would (unfortunately) think about. The two numbers I’ve written here correspond to the values of the Hubble constant, a cosmological parameter that defines the present expansion rate of the universe.

The units for this constant are a little bit strange, namely km s-1 Mpc-1 (which if you simplify, becomes s-1, or Hertz (frequency)?!). Essentially, what it means is that if you place a stationary object 1 Mpc away (roughly 3.16 million light years away), that object will appear to be receding away from you at a speed equal to the Hubble constant solely due to the expansion of the universe.

The problem that scientists are trying to solve is that there is a large difference between the measurements for this value based on the cosmic microwave background and based on galaxies and supernovae. This is called the Hubble tension, and it’s a very big deal within the cosmology community as the acceptance of one value over another could mean redefining our model of the universe.

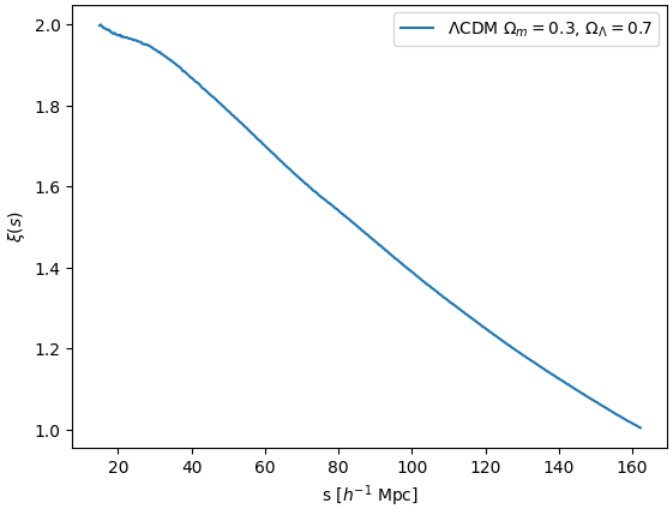

Observations of the early universe, mainly from the cosmic microwave background, measured by missions like Planck and DESI, suggest a slower expansion rate of around 67 km s-1 Mpc-1. Meanwhile, measurements of the late universe, using supernovae, Cepheid stars, and other distance indicators, consistently give a faster rate of about 72 km s-1 Mpc-1. This 2.2-sigma deviation has persisted despite improved measurements, suggesting that either there are unknown systematic errors in one or both methods, or our current cosmological model (ΛCDM) might be missing new physics, such as exotic dark energy behavior or additional relativistic particles in the early universe.

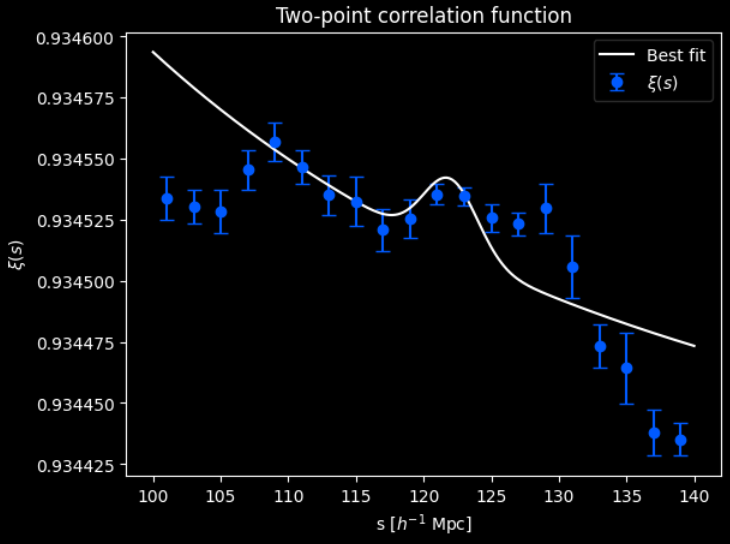

If you’ve been reading my other posts, my series on DESI DR1 aims to help contribute to the existing studies of the Hubble constant by computing the value at high redshifts from the latest publicly available data.