When I first peered through my backyard telescope at the faint smudge of the Andromeda Galaxy, I wasn’t just looking outward. Instead, I was searching inward, wondering whether somewhere in that sea of stars, another child might be gazing back, asking the same question: Are we alone? Lisa Kaltenegger’s Alien Earths: The New Science of Planet Hunting and the Search for Life Beyond Earth doesn’t just answer that question, it reframes it, transforming cosmic wonder into a rigorous, hopeful, and deeply human scientific quest.

Kaltenegger, a leading astrophysicist and director of the Carl Sagan Institute, writes with the clarity of a teacher and the passion of a pioneer. She guides readers through the evolution of exoplanet science – from the first wobbles detected in distant stars to the atmospheric fingerprints of potentially habitable worlds. What makes Alien Earths exceptional is not just its scientific depth, but its narrative arc: it’s the story of how humanity learned to see planets we cannot visit, using light bent by gravity and spectra split by prisms, all to answer an ancient question with modern tools.

Reading this book felt like a conversation with a mentor who understands both equations and emotions. Kaltenegger doesn’t shy away from uncertainty; she embraces it as the engine of discovery. When she describes how the James Webb Space Telescope might one day detect bio-signatures – oxygen, methane, or even industrial pollutants – in an exoplanet’s atmosphere, she doesn’t promise aliens. Instead, she offers something more profound: a methodology for hope grounded in evidence.

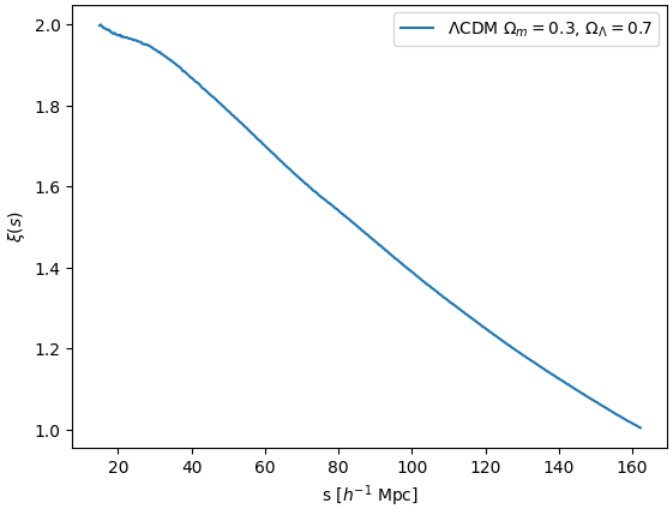

This resonated deeply with my own journey. Like Kaltenegger, I began with awe – a six-year-old mesmerized by black holes at the Air and Space Museum – and gradually learned that wonder must be paired with work. In my high school astronomy club, I’ve tried to emulate her spirit: not just showing Saturn’s rings, but explaining how we know they’re there. Similarly, while analyzing public datasets on detecting Baryon Acoustic Oscillations at high redshift range, I’ve wrestled with noise, calibration, and false results —experiences Kaltenegger vividly recounts from the front lines of planet hunting. Her book validated that frustration is part of the process; every ambiguous signal is a step toward clarity.

One of Alien Earths’ most compelling insights is its emphasis on Earth as a template – and a warning. Kaltenegger shows how studying Earth’s own atmospheric evolution helps us interpret alien skies, but also reminds us that habitability isn’t guaranteed. A planet in the “Goldilocks zone” may still be barren, just as Earth itself has teetered on the edge of catastrophe. This duality struck me as I stood on a golf course last spring, watching a thunderstorm roll in: even our stable-seeming world is dynamic, fragile, and rare. Kaltenegger’s vision isn’t just about finding Earth 2.0—it’s about understanding what makes Earth 1.0 worth protecting.

Alien Earths is more than a science book; it’s a call to participate. Kaltenegger writes not as a distant authority, but as an explorer inviting us aboard. For students like me – tutoring in math, coding simulations, or organizing telescope nights – her message is empowering: the search for life beyond Earth belongs to all of us. It requires coders, educators, engineers, and dreamers.

In the end, this book is a perfect reflection of why I keep looking up. The night sky is a laboratory, a testing ground, and a community. Lisa Kaltenegger’s Alien Earths is an essential guide to that cosmos, reminding us that the search for other worlds is, ultimately, a profound journey to understand our own. It is a compelling, hopeful, and brilliantly accessible work that will leave you gazing at the stars with a renewed sense of purpose and wonder.